The villages we visited (Kuppaiyanallur & Poonthandallum), each of which is about 90 minutes drive from seaside resorts, lie squarely in India's extremely-impoverished farming interior. The access road was generally unpaved and often washed-out. Cash crop rice paddies and sugar cane fields stretch for miles, accented by the occasional crop of peanuts or vegetables. Upon our arrival, it was clear that these villages are much less fortunate than the eChoupal community we visited in Hathras.

The villages we visited (Kuppaiyanallur & Poonthandallum), each of which is about 90 minutes drive from seaside resorts, lie squarely in India's extremely-impoverished farming interior. The access road was generally unpaved and often washed-out. Cash crop rice paddies and sugar cane fields stretch for miles, accented by the occasional crop of peanuts or vegetables. Upon our arrival, it was clear that these villages are much less fortunate than the eChoupal community we visited in Hathras. Although the children are full of joy and the elders are hospitable and proud of their homes, the homes themselves are largely mud and thatch huts -- many of which are collapsing on one or more sides. On the ground outside of one home lay an emaciated grandfather, apparently too weak to eat. Even if they had money for a doctor, the nearest hospital is nearly 100km away. Ambulance services are unavailable and nobody in the village owns a car. The only road transport is a daily bus service taking commuters back-and-forth to Chennai.

Although the children are full of joy and the elders are hospitable and proud of their homes, the homes themselves are largely mud and thatch huts -- many of which are collapsing on one or more sides. On the ground outside of one home lay an emaciated grandfather, apparently too weak to eat. Even if they had money for a doctor, the nearest hospital is nearly 100km away. Ambulance services are unavailable and nobody in the village owns a car. The only road transport is a daily bus service taking commuters back-and-forth to Chennai. We asked villagers what they need the most and they knew exactly what was lacking: jobs/education/clean water -- but mostly jobs. As we've seen elsewhere in developing regions, young wage earners are leaving the villages en masse and although they may send money home from their jobs in the city, they never bring productive jobs back to the villages. One such expat, Lawrence, who works at our hotel in Mamallapuram earns a healthy wage of 2000 rupees/month ($52) which is apparently enough to support a family and to send money home to his parents in Kuppaiyanallur. (His parents and sister must earn significantly less than this doing backbreaking labor on the crops year-round.)

We asked villagers what they need the most and they knew exactly what was lacking: jobs/education/clean water -- but mostly jobs. As we've seen elsewhere in developing regions, young wage earners are leaving the villages en masse and although they may send money home from their jobs in the city, they never bring productive jobs back to the villages. One such expat, Lawrence, who works at our hotel in Mamallapuram earns a healthy wage of 2000 rupees/month ($52) which is apparently enough to support a family and to send money home to his parents in Kuppaiyanallur. (His parents and sister must earn significantly less than this doing backbreaking labor on the crops year-round.)A related problem in the villages is alcoholism. We met two mothers (of two and four children, respectively) who were supporting their families independently after the childrens' fathers had died of alcohol poisoning. Apparently, the lack of entertainment options in the villages, coupled with lump-sum paydays when crops are sold and cheap low-quality grain alcohol makes for a deadly combination for men in the villages around harvest time. Their widows receive no official support from the state or the village and they have no real hope of re-marriage. The women we met with were managing to feed their young families by weaving, but just barely.

So what are we going to do about what we've seen and learned? We wanted to give everyone in the village our card and to tell them that we'd be sending eChoupal, SKS, ICICI, FabIndia and LifeSpring to solve their problems in the following week, but we could make no such promises. Many of the companies we visited on our trip offer solutions ranging from microfinance & small business loans to sustainable local craftwork jobs that would greatly improve the lives of the Tamil villagers. Upon our departure, we pledged to do whatever we can to connect these companies and villages as quickly as possible. If you have ideas or would like to assist, we'd love your support!

So what are we going to do about what we've seen and learned? We wanted to give everyone in the village our card and to tell them that we'd be sending eChoupal, SKS, ICICI, FabIndia and LifeSpring to solve their problems in the following week, but we could make no such promises. Many of the companies we visited on our trip offer solutions ranging from microfinance & small business loans to sustainable local craftwork jobs that would greatly improve the lives of the Tamil villagers. Upon our departure, we pledged to do whatever we can to connect these companies and villages as quickly as possible. If you have ideas or would like to assist, we'd love your support!As always, pictures tell the rest of the story:

Rice farmers bringing the harvest to the road to separate the seed from the chaff. We saw several methods in-use on our trip, ranging from manual separation to placing the dry rice stalks on the road for passing cars to roll across.

Rice farmers bringing the harvest to the road to separate the seed from the chaff. We saw several methods in-use on our trip, ranging from manual separation to placing the dry rice stalks on the road for passing cars to roll across.  Goat herders dotted the landscape between farms. According to Lawrence, these landless herders are among the poorest residents of Tamil Nadu.

Goat herders dotted the landscape between farms. According to Lawrence, these landless herders are among the poorest residents of Tamil Nadu. Lawrence confided that the man on the motorcycle was a moneylender who was making his weekly rounds to collect payments from villagers. The shouting between the lender and his (presumably penniless) borrower was heartbreaking. Although we did not find out how much interest was being charged on this particular loan, these sorts of lenders typically charge several thousand percent annually -- hardly a rate that allows borrowers to payoff the loan successfully -- but sadly these are often the only terms on which farmers can borrow.

Lawrence confided that the man on the motorcycle was a moneylender who was making his weekly rounds to collect payments from villagers. The shouting between the lender and his (presumably penniless) borrower was heartbreaking. Although we did not find out how much interest was being charged on this particular loan, these sorts of lenders typically charge several thousand percent annually -- hardly a rate that allows borrowers to payoff the loan successfully -- but sadly these are often the only terms on which farmers can borrow. Two monks standing proud near the entrance to a Hindu temple. Thirty seconds earlier, both had been talking boisterously on cell phones nearby.

Two monks standing proud near the entrance to a Hindu temple. Thirty seconds earlier, both had been talking boisterously on cell phones nearby. A fisherman pushing his raft across the waterway between the mainland and an outer reef. This area bore the full force of the tsunami that made headlines in late 2004.

A fisherman pushing his raft across the waterway between the mainland and an outer reef. This area bore the full force of the tsunami that made headlines in late 2004. Family of five on a motorcycle going 65kph on the highway. This is proof that the Indian government hasn't invested much in its families (school, social security, health care). If it had, there would be better safety enforcement to ensure that the investment doesn't tip over and skitter across the pavement in a mass of blood and metal.

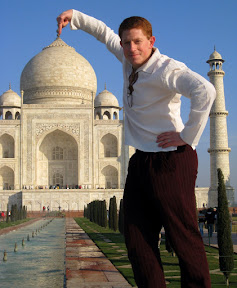

Family of five on a motorcycle going 65kph on the highway. This is proof that the Indian government hasn't invested much in its families (school, social security, health care). If it had, there would be better safety enforcement to ensure that the investment doesn't tip over and skitter across the pavement in a mass of blood and metal. Mamallapuram is known for its ancient stone monuments. Although the brochure says that the carvings date back to the 7th century, it is clear that there has been quite a bit of upkeep and enhancement added since the tourists began rolling in.

Mamallapuram is known for its ancient stone monuments. Although the brochure says that the carvings date back to the 7th century, it is clear that there has been quite a bit of upkeep and enhancement added since the tourists began rolling in. Like many of the monkey handlers we'd seen previously, this man had trained his companion to do somersaults and dance... although it is clear from the expression on the monkey's face that the training regimen consisted of more sticks than carrots.

Like many of the monkey handlers we'd seen previously, this man had trained his companion to do somersaults and dance... although it is clear from the expression on the monkey's face that the training regimen consisted of more sticks than carrots. Professor Gita Johar's mother hosted us for an evening at her home in the Mylapore district of Chennai, complete with dinner and a trip to a local Indian dance performance. Dinner was delicious and we were thrilled at the opportunity to eat fresh vegetables for the first time in several weeks.

Professor Gita Johar's mother hosted us for an evening at her home in the Mylapore district of Chennai, complete with dinner and a trip to a local Indian dance performance. Dinner was delicious and we were thrilled at the opportunity to eat fresh vegetables for the first time in several weeks.  For those of you who have been wondering what to do will all that cow urine that keeps accumulating around the house, this poster outlines the curative properties of cow urea ranging from blood purification to bile stabilization and removal of kidney stones. Drink up!

For those of you who have been wondering what to do will all that cow urine that keeps accumulating around the house, this poster outlines the curative properties of cow urea ranging from blood purification to bile stabilization and removal of kidney stones. Drink up! Our final sunrise in India on the beach in Mamallapuram with Dimitra behind a fishing boat. Many of these boats were donated by western philanthropists and (oddly) German tech company SAP following the tsunami that devastated the local industry.

Our final sunrise in India on the beach in Mamallapuram with Dimitra behind a fishing boat. Many of these boats were donated by western philanthropists and (oddly) German tech company SAP following the tsunami that devastated the local industry.Be sure to check out pictures from the entire group online: http://picasaweb.google.com/socialindia. We'll be adding albums over the next few weeks, so keep checking for updates through the end of February.

Also be sure to check out Dimitra's personal blog from the entire trip: http://dimitradefotis.blogspot.com/

Nalladhum Nandri, (Tamil for "goodbye and thank you")